This next illustration for the HCSB Study Bible features a montage of the various items contained within the Mosaic Tabernacle: the ark of the covenant, the bronze laver, the bronze altar, the golden incense altar, the golden lampstand and the golden table of shewbread. (See Exodus 25-30; 36-40 for descriptions of their appearance and construction.) Although this illustration as a whole underwent very little transformation or development following the initial sketch (below), there was a good deal of thought and research put into each of the individual elements prior to that point.

In terms of general aesthetics, it is generally agreed among scholars that the tabernacle and its items would have been highly influenced by Egyptian art, since this would have been the only style that the Hebrews would have had exposure to for over 400 years. Furthermore, it is likely that the superintendent Bezalel and some of his fellow craftsmen would have been formally trained in the Egyptian canons and techniques. (Of course, God gave Moses very specific directions for the construction of each item, which probably went beyond the measurements and simple descriptions mentioned in the text itself to include detailed visions of the items in toto. These fully-realized visions could of course have employed any style whatsoever, whether known or unknown to the Israelites, or to any other people, prior to that time, and could have guided Moses as he in turn guided the craftsmen. Nevertheless, it seems likely that an Egyptian style prevailed, and the whole question of employing or importing a “pagan” style or aesthetic heritage into the worship of Yahweh makes for some interesting theological discussions, and has been treated by Francis Schaeffer, Gene Edward Veith, and others.)

At any rate, fabulous examples of Egyptian art from the time period abound, especially among the artifacts from the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, which include several items of similar construction to some of the tabernacle furnishings. Some items posed greater and more interesting creative challenges than others to my attempts to both faithfully and imaginatively represent them. The laver, for instance is scantily described (Ex. 30:17-21; 38:8), but it seems to have had a supporting base that was distinct from the basin itself, though the two presumably functioned and were transported as a single unit.

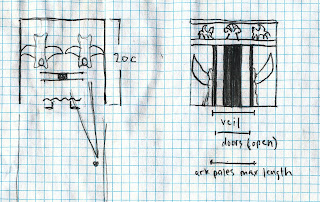

The ark of the covenant was of course an object of special attention. While it was tempting to make it look just like the version in the Indiana Jones movies, which I think is a splendid and probably a reasonably accurate representation, I did have a few twists of my own that I wanted to lend to my own interpretation. I worked some of these out in a larger sketch (below). First off, it seems that cherubim are presented, both biblically and extra-biblically, as winged, sphinx-like creatures, with the head of a man and the body of some four-footed animal, typically a lion or a bovine. (Parallel examples abound in the art of numerous cultures, including Egyptian, Phoenician, Assyrian, Babylonian and Greek.) The Bible speaks of the lid of the ark as the “mercy seat”, and a seat is actually what it was: the cherubim spread out their wings to serve as a throne upon which the presence of Yahweh Himself was seated. (Perhaps the cherubs’ wings surrounded or enveloped an actual throne or seat, though I did not include one.)

The question of the ark’s orientation (did the carrying poles go in the long or the short side?) is particularly consternating, as I’ll explain in more detail when discussing the sketches for the Temple of Solomon, and I’m still not settled on the answer to that one. (You can see that I actually switched the orientation even here.) The relief-sculptured motif on the ark’s front is purely my own imagining, but is an exploration of how the exodus event might have been captured in visual terms. You have the parting waters of the Red Sea, re-birthing Israel as a nation, and the two tablets of the Decalogue, overshadowed by pyramid-shaped mountains. These recall both the land of Egypt that had been left behind (pyramids are stylized, man-made mountains, after all) and Mount Sinai (with the glory of God streaming from the top), where Israel’s identity as Yahweh’s Covenant Nation was formally established.